Plastic floating at sea often winds up in debris-filled gyres, commonly known as garbage patches. These patches of plastic circulating in the ocean pose a danger to wildlife and are slowly entering the food chain. One project aims to remove this debris with floating boom technology, which is often used to contain oil spills.

Ocean Gyres: Trapping Debris to Form Garbage Patches

Ocean gyres are large systems of circular currents that are created by Earth’s wind patterns and rotation and affected by landmasses. The water moves in the direction that the wind blows, and the planet’s rotation changes the direction of the currents due to the Coriolis effect. There are five major gyres on Earth, located in the:

- North Atlantic Ocean

- South Atlantic Ocean

- North Pacific Ocean

- South Pacific Ocean

- Indian Ocean

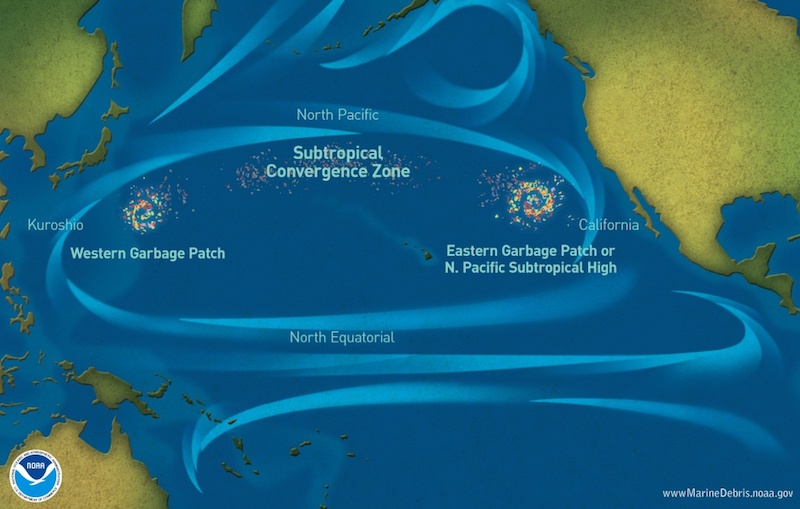

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is located within the North Pacific Gyre, which binds the convergence of debris so that the plastic particles become trapped in the center. The patch is a massive collection of marine debris extending from the west coast of North America to Japan.

Map of the North Pacific subtropical convergence zone, where the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is located. Image by NOAA and in the public domain in the United States, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Problem with the Garbage Patch

Although the area of trash floating in the North Pacific Ocean is huge, it’s not always easy to predict the garbage patch’s exact location on any given day. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), this is because the type of litter and the borders around the concentrations of the debris are constantly changing with the ocean currents and winds. To complicate matters, the longer plastics remain in the ocean, the more likely they are to break down and degrade into microplastics.

The naming of the great patch may, in fact, be misleading, as the most concentrated areas of plastics are often composed of particles too small to see in aerial photographs. In addition, many of these small particles (which can be less than 1 millimeter in size) are found under the ocean surface than above, with many particles sinking to the ocean floor. Ships can often sail through a patch just fine along the water’s surface, their crews never realizing that a veritable iceberg of debris is right below.

Microplastics typically found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Image by the NOAA Marine Debris Program — Own work. Licensed under CC BY 2.0, via Flickr Creative Commons.

While we may not always be able to see the plastic, the particles trapped within and between gyres are detrimental to marine life and can cause harm to the environment. For instance, various species of fish living in the mesopelagic layer of the gyre migrate between the ocean surface and deeper waters as night turns to day. Scientists found that when they collected fish from this layer, many of them had eaten plastic in the gyre. From their estimation, fish from the gyre consume 12,000 to 24,000 tons of plastic per year — a good indication that plastic has entered the food chain.

Booming Technology Enables Ocean Cleanup Efforts

While manual efforts by divers have made great strides to remove plastic, fishing nets, and other debris, engineers are looking to create cleanup technology that can address the masses of garbage on a larger scale. One source of inspiration is containment boom designs. A containment (or floating) boom is a type of floating barrier often used to contain oil spills. In cases where there are large amounts of trash and debris, a net or skirt is attached to capture the debris at and under the water’s surface.

NOAA divers removing debris in the northwestern Hawaiian islands. Image by NOAA Marine Debris Program and in the public domain, via Flickr Creative Commons.

A nonprofit called The Ocean Cleanup is designing and deploying a boom to contain the ~1.8 trillion pieces of plastic and debris that form the Pacific patch (an area twice the size of Texas!). The boom tube for this floating system measures nearly 2000 feet.

To begin such a massive undertaking, researchers conducted several expeditions to retrieve plastic from the ocean, measure the vertical distribution of plastic at sea, and obtain samples and measurements of the particles. In order to do this, The Ocean Cleanup designed a trawl that could be towed alongside a vessel and measure microplastic concentrations. They then conducted a follow-up study, finding that conventional measurement methods often underestimate microplastic loads by up to 97%. The reason is that most sampling devices do not account for the ocean mixing processes that plunge a lot of plastic below most devices.

After analyzing plastic particle samples and mapping the concentration and area of the patch in the Pacific Ocean, engineers created a scale model of a containment boom, applying various types of waves and load conditions. A small-scale prototype was then ready for a test in the open waters of the North Sea. This test helped the engineers to optimize the material used for the boom design. They also decided to change the design from a moored system to a free-floating system.

An example of a boom tow tugging a floating boom. Image by the U.S. Navy and in the public domain in the United States, via Wikimedia Commons.

In September of 2018, the giant floating boom system was towed 300 miles offshore from San Francisco Bay. After monitoring the system to see how it fared in the ocean, the engineers gave the go-ahead to tow the system another 1000 miles toward the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, with the floating pipe system arriving at its destination in October of 2018. Ideally, if the system is able to sufficiently collect debris, ships can come along every few months to take the garbage from the containment system and transport it back to land for recycling.

Although there are concerns about how this project might impact marine life and the limits of the floating boom’s ability to remove plastics below the water’s surface, designs such as this one present possible solutions to the problem of debris getting trapped in ocean gyres.

Suggested Reading

- Read this blog post on removing microplastics from wastewater: Analyzing Wastewater Contaminant Removal in a Secondary Clarifier

- Learn about modeling water waves with the KdV Equation:

Comments (0)