A pioneer in chemistry, sanitary engineering, and human ecology, Ellen Swallow Richards paved the way for women in science. She was the first woman to attend, graduate, and teach at MIT. During her career, she developed standards for water quality and isolated the chemical element vanadium. In addition, Richards was passionate about using science to create a better home life, founding the field of home economics.

Ellen Swallow Richards: Leading the Way for Women in Science

Ellen Swallow Richards (née Ellen Swallow) was born on December 3, 1842, in Dunstable, Massachusetts. For much of her life, she was homeschooled by her parents, Peter and Fanny Swallow, both of whom were teachers. After briefly attending and graduating from Westford Academy, Richards began working in order to save money for college.

At age 26, she became a student at Vassar College, where she earned a BS in chemistry. Soon after, Richards applied to be an apprentice for several chemists around Boston. Although she was rejected, one pair advised her to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), then known as the Institute of Technology of Boston. Until this point, no science school in the United States had ever accepted a woman, but MIT made an exception for Richards, allowing her in as a “special student.” She soon proved her place and became a full student, graduating in 1873 with a BS in chemistry. That same year, she also earned an MA from Vassar. (Much later, in 1910, Smith College awarded her an honorary doctorate degree.)

Left: Ellen Swallow Richards. Image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Woodward’s Mill Pond, which is near Swallow Union Elementary School in Dunstable, MA. The school was named after Ellen Swallow.

In 1875, Ellen Swallow married Robert Richards, a professor in the Mining Engineering Department at MIT. Her marriage afforded her more financial freedom and she used this to promote women’s education in science. Richards spoke with the Woman’s Education Association of Boston, persuading them to donate to the creation of a laboratory for women. Located at MIT, the lab was led by Professor John Ordway, with Richards acting as assistant director and an instructor. For seven years, she taught classes on chemistry, mineralogy, and more — without pay. In fact, she contributed $1,000 per year to the Women’s Laboratory. She worked there until the laboratory shut down in 1883, when MIT started to regularly accept female students.

During this time, Richards cofounded the American Association of University Women. She also taught women who couldn’t attend MIT in person, working with the Society to Encourage Studies at Home to send science lessons along with equipment (like microscopes) to students via mail.

Testing the Waters of Massachusetts

During the 1880s, MIT set up a laboratory for sanitary chemistry, appointing Richards as an instructor. One of her first projects was for the State Board of Health of Massachusetts, which wanted to survey local waters from around the state for pollution. With her assistants, Richards tested ~40,000 samples for waste and sewage, an amount that surpassed the scale of any previous study.

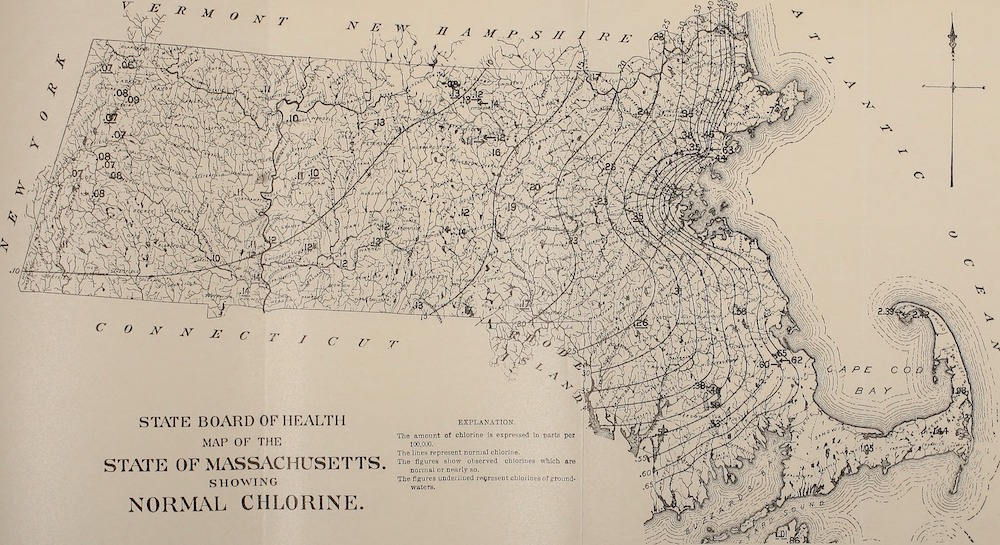

Richards’ map of the normal chlorine in Massachusetts, which appeared in her book Air, Water, and Food from a Sanitary Standpoint. Image in the public domain, via Flickr Creative Commons.

By taking meticulous notes of the results, Richards was able to plot normal chlorine concentrations from the ocean in waters across Massachusetts. This normal chlorine map could help determine the influence of human pollution: All you needed to do was compare a body of water’s actual chloride count to that on the map. As a result of her work, the state implemented the first water quality standards in the U.S. as well as set up the first modern sewage treatment plant.

Applying Science to the Home

Richards was a firm believer in the practical applications of chemistry, particularly when it came to domestic life. To promote better living, she took it upon herself to test food, fabrics, and other consumer products, which weren’t regulated at the time. She used chemical analysis to find contaminants like mahogany sawdust and sand in cinnamon and sugar, as well as more harmful toxins like arsenic in wallpaper. This work inspired her to write the book Food Materials and Their Adulterations, which led to the first Pure Food and Drug Act in Massachusetts.

Ellen Swallow Richards conducted many experiments in her own home, shown here. Image by Jameslwoodward — Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In addition, Richards helped found the New England Kitchen of Boston, a takeout restaurant that used science to develop healthy meals for affordable prices. Her work eventually inspired the first major lunch program in America, which provided low-cost (or free) nutritious meals to students. She was also asked to represent Massachusetts during the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, where she was in charge of the Rumford Kitchen, a demo of applying chemistry to cooking.

Richards didn’t limit herself to testing food quality: She also conducted studies of air quality and investigated how to best ventilate a home, how much gas is needed for various chores, and the chemistry of cleaning. Her dedication to promoting healthier living at home established the field of home economics, and she became the first president of the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences (then the American Home Economics Association). In addition, she established the Journal of Home Economics as well as the American Kitchen Magazine.

Other Notable Accomplishments

A woman of many interests, Richards also worked with minerals. In 1872, she discovered insoluble residue in samarskite, which led her to believe that it contained yet unknown elements. A few years later, two elements, samarium and gadolinium, were discovered in the mineral. What’s more, Richards was the first to isolate vanadium and developed a technique to find out how much nickel is in ores. For her work in mineralogy, the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers invited her to become their first female member.

Richards introduced two terms in English: ecology and euthenics. The first, originally spelled “oekology,” was thought up by German biologist Ernst Haeckel. With Haeckel’s permission, Richards brought “ecology” to America and developed the field, including the role that humans play in her definition (now known as human ecology). While the word “ecology” caught on, Richards’ vision of the field didn’t have the same success and for a long time, the subject focused only on the relationships in nature.

As for euthenics (not to be confused with eugenics), this was a word Richards herself coined to mean “the betterment of living conditions, through conscious endeavor, for the purpose of securing efficient human beings.” Due to its broad scope, this term didn’t have the same success as ecology, but it’s the one that truly sums up Richards’s life work.

Thanks to Richards’s many achievements, we now have quality standards for air, water, and food, making for better living conditions. In addition, much of our common knowledge about cooking and cleaning is due to Richards, as she was one of the first to apply chemistry to explain the science of nutrition and other such fields.

In honor of her accomplishments, let’s wish Ellen Swallow Richards a happy birthday!

Further Reading

- Find out more about Ellen Swallow Richards from these sources:

- Read about other influential women in STEM:

- Check out more topics related to food science on the COMSOL Blog

Comments (0)